Changing the priority of processes

Processes on a Linux system can be run with an altered priority, giving some processes more priority and others less. This gives you, the administrator, full reign when it comes to ensuring that the most important processes on the system are running with an adequate level of prioritization. There are dedicated commands for this purpose: nice and renice. These commands allow you to launch a process with a specific priority, or change the priority of a process that’s already running.

Nowadays, manually editing the priority of a process is something administrators will find themselves doing less often than they used to. A processor with 32 cores (or many more) is not all that uncommon, and neither is hundreds of gigabytes of RAM. Servers nowadays are certainly more powerful than they used to be, and are nowhere near as resource-starved as machines of old. Many servers (such as virtual machines) and containers are dedicated to a single task, so process tuning may not be of extreme value anymore. However, data processing firms and companies utilizing deep learning functions may find themselves needing to fine-tune some things.

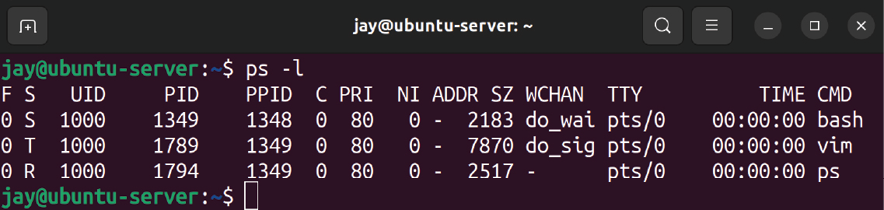

Regardless of whether or not prioritizing processes is something that will be immediately useful to you, it’s a good idea to at least understand the concept just in case you do find yourself needing to increase or decrease the priority of a process some day. Let’s revisit the ps command, this time with the -l argument:

ps -l

The output of this command will appear as follows:

Figure 7.5: The output of the ps -l command

With the output of the ps -l command, notice the PRI and NI columns. PRI refers to the priority, and NI pertains to the “niceness” value, which we’ll discuss in more detail later in this section. In this example, each process that I’m running has a PRI of 80, and an NI of 0. I didn’t change or alter any of these; these are the values that I get when I start processes with no special tweaks. A PRI value of 80 is the starting value for that value on all processes, and will change as we increase or decrease the niceness value.

As I mentioned, we have dedicated commands that allow us to alter priorities, nice and renice. To determine which to use, it all comes down to whether or not the process is already running. With regard to the processes listed in Figure 7.5, we would want to use renice to change the priority for those, since they’re all already running. If we wanted to launch a process with a specific priority right from the beginning, we would use nice instead.

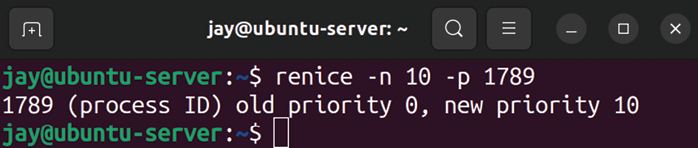

For example, let’s change the process of the vim session I have running. Sure, this is a somewhat lame example, as vim isn’t a very important process. In the real world, you’d be prioritizing processes that are actually important. In my case, since the vim process has a PID of 1789, the command I would need to run in order to change the niceness would become this:

renice -n 10 -p 1789

The output of this command will appear as follows:

Figure 7.6: Changing the priority of a process with renice

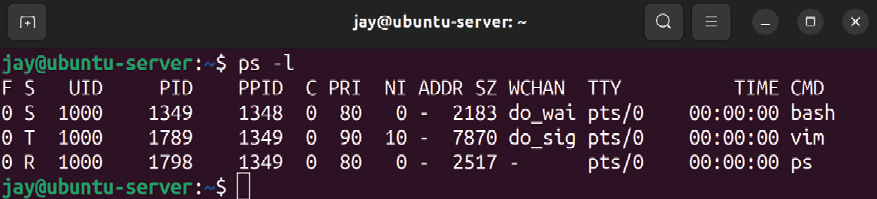

If we run ps -l again, we can see the new nice value for vim:

Figure 7.7: The output of the ps -l command after changing the priority of a process

The new nice value of 10 now shows up for vim under NI, and the PRI value has increased to 90. Now, this instance of vim will run at a lower priority than my other tasks, the reason being that the higher the nice value, the lower the priority. Notice that I didn’t use sudo with the command when I changed the priority. In this example, that’s okay because I’m increasing the nice value of the process, and that’s allowed. However, let’s try to decrease the nice value without sudo, using the following command:

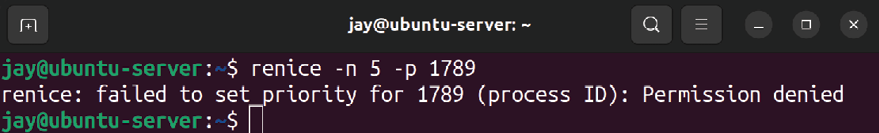

renice -n 5 -p 1789

As you can see in the following output, I won’t be as successful:

Figure 7.8: Attempting to decrease the priority of a process

My attempt to decrease the nice value from 10 down to 5 was blocked. If I were able to lower the niceness, then my process would be running at a higher priority. Instead, I received a Permission denied error. So essentially, users are allowed to increase the niceness of their processes, but are not allowed to decrease it, not even for processes they’ve initiated themselves. If you wish to decrease the nice value, you’ll need to do so with sudo. So essentially, if you want to be “nicer,” you can go ahead and do so. If you wish to be “meaner,” you’ll need root privileges. In addition, a user won’t be able to change the priority of a process they don’t own. So, if you attempt to use renice to change the niceness of a task running as a different user, you’ll receive an Operation not permitted error.

At this point, we know how to re-prioritize our running processes with renice. Now, let’s take a look at starting a new process with a specific priority with nice. Consider the following command:

nice -n 10 vim

Here, we’re launching a new instance of vim, but with the priority set to a specific value right from the start. If we want to change the priority of vim again later, we’ll need to use renice. As I mentioned earlier, nice is used to launch a new process with a specific priority, and renice is for changing the priority of a pre-existing process. In this example, we launched vim and set its nice value to 10 in one command.

Changing the priority of a text editor such as vim may seem like an odd choice for a test case, and it is. But the vim editor is harmless, as the likelihood of us changing the priority of it leading to a system halt is extremely minimal. There’s no practical reason I can think of where it would be useful to re-prioritize something like a text editor. The takeaway, though, is that you can change the priority of the processes running on your server. On a real server, you may have an important process that runs and generates a report, and that report must be delivered on time. Or perhaps you have a process that generates an export of data that a client needs to have in order to make an on-time deliverable. So, if you think of the bigger picture, you can replace vim with the name of a process that is actually important for you or your organization.

You might be wondering what “nice” means in the context of the nice and renice commands. The “nice” number essentially refers to how nice a process is to other users. The higher the nice value, the lower the priority. So, a value of 20 is nicer than a value of 10. In that case, processes with a niceness of 20 are running at a lower priority, and so are kinder to the other processes on the system. The niceness can range from -20 to 19. A process with a nice value of -20 is the highest priority possible, while 19 is the lowest priority it can have. The entire system is quite a bit more complicated than this simple description. Although I refer to the nice value as the priority, it actually isn’t. The nice value is used to calculate the actual priority. But for now, if we simplify the nice value to be representative of the priority, and the nice value to equate to a lower priority, the higher the number gets, that’s enough for now.

So far, we’ve been using the nice and renice commands along with the -n option to set the nice values directly. It may be interesting to note though that you can simplify the renice command and leave out the -n option:

renice 10 42467

That command sets the nice value of the process to a positive 10, similar to our other examples. We can also use a negative number for the niceness if we want to increase the priority:

sudo renice -10 42467

Although it doesn’t save us much typing to leave out the -n option, now you know that it is a possibility. The other difference with that example was that I needed to use sudo since I’m decreasing the nice value (more on that later).

When it comes to the nice command, we can also leave out the -n option, but the command works a bit differently in this regard. The following won’t work:

nice 15 vim

The syntax of nice is a bit different, so giving it a positive number directly won’t work as it does with renice. For that, we’ll need to add a hyphen in front:

nice -15 vim

When you look at that command, you may assume we’re applying a negative number. Actually, that’s not true. Since the syntax is different with nice, the -15 value we used results in a positive 15. We needed the hyphen in front of the value to signify to nice that we’re applying a value as an option. If we actually do want to use a negative value with nice while also avoiding the -n option, we would need to use two hyphens:

nice --10 vim

The difference in syntax between the two commands with the -n option is a bit confusing in my opinion, so I recommend simply using the -n option with nice and renice, as that’s going to be more uniform between them:

nice -n 10 vim

sudo nice -n -10 vim

renice -n 10 42467

sudo renice -n -10 42467

Those examples show both nice and renice using the -n option, and setting both positive and negative values. Since the -n option is used the same way between the two commands, it may be easier to focus on committing that to memory rather than focusing on the specifics. As previously discussed, I used sudo with commands that set a negative value for niceness, since only root can change a process to, or start a process with, a niceness below 0. You’ll receive the following error if you try to do it anyway:

nice: cannot set niceness: Permission denied

This type of protection is somewhat important, because you may have some users who feel as though their processes are the most important, and try to prioritize them all the way to -19. At the end of the day, it’s better for a system administrator to make decisions on which processes are allowed to reach a niceness value in the negative.

As an administrator of Ubuntu servers, it’s up to you to decide which processes should be running, and at what priority. You’ll then determine the best way to achieve the exact system state that’s appropriate, and tuning process priority may be a part of that. If nothing else, learning the nice and renice commands gives you another utility for your toolset.