A functional solution to our problem

Let’s try to be more general; after all, requiring that some function or other be executed only once isn’t that outlandish, and may be required elsewhere! Let’s lay down some principles:

- The original function (the one that may be called only once) should do whatever it is expected to do and nothing else

- We don’t want to modify the original function in any way

- We need a new function that will call the original one only once

- We want a general solution that we can apply to any number of original functions

A SOLID base

The first principle listed previously is the single responsibility principle (the S in the SOLID acronym), which states that every function should be responsible for a single functionality. For more on SOLID, check the article by Uncle Bob (Robert C. Martin, who wrote the five principles) at butunclebob.com/ArticleS.UncleBob.PrinciplesOfOod.

Can we do it? Yes, and we’ll write a higher-order function, which we’ll be able to apply to any function, to produce a new function that will work only once. Let’s see how! We will introduce higher-order functions in Chapter 6, Producing Functions. There, we’ll go about testing our functional solution, as well as making some enhancements to it.

A higher-order solution

If we don’t want to modify the original function, we can create a higher-order function, which we’ll (inspiredly!) name once(). This function will receive a function as a parameter and return a new function, which will work only once. (As we mentioned previously, we’ll be seeing more of higher-order functions later; in particular, see the Doing things once, revisited section of Chapter 6, Producing Functions).

Many solutions

Underscore and Lodash already have a similar function, invoked as _.once(). Ramda also provides R.once(), and most FP libraries include similar functionality, so you wouldn’t have to program it on your own.

Our once() function may seem imposing at first, but as you get accustomed to working in an FP fashion, you’ll get used to this sort of code and find it to be quite understable:

// once.ts

const once = <FNType extends (...args: any[]) => any>(

fn: FNType

) => {

let done = false;

return ((...args: Parameters<FNType>) => {

if (!done) {

done = true;

return fn(...args);

}

}) as FNType;

};

Let’s go over some of the finer points of this function:

- Our

once()function receives a function (fn) as its parameter and returns a new function, of the same type. (We’ll discuss this typing in more detail shortly.) - We define an internal, private

donevariable, by taking advantage of closure, as in Solution 7. We opted not to call itclicked(as we did previously) because you don’t necessarily need to click on a button to call the function; we went for a more general term. Each time you applyonce()to some function, a new, distinctdonevariable will be created and will be accessible only from the returned function. - The

returnstatement shows thatonce()will return a function, with the same type of parameters as the originalfn()one. We are using the spread syntax we saw in Chapter 1, Becoming Functional. With older versions of JavaScript, you’d have to work with the arguments object; see developer.mozilla.org/en/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Functions/arguments for more on that. The modern way is simpler and shorter! - We assign

done = truebefore callingfn(), just in case that function throws an exception. Of course, if you don’t want to disable the function unless it has successfully ended, you could move the assignment below thefn()call. (See Question 2.4 in the Questions section for another take on this.) - After the setting is done, we finally call the original function. Note the use of the spread operator to pass along whatever parameters the original

fn()had.

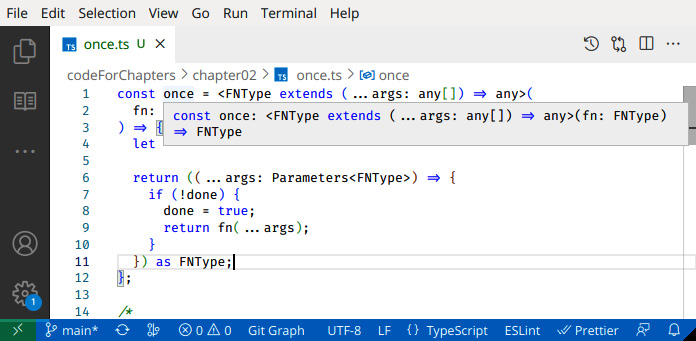

Typing for once() may be obscure. We have to specify that the type of the input function and the type of once() are the same, and that’s the reason for defining FNType. Figure 2.2 shows that TypeScript correctly understands this (Check the answer to Question 1.7 at the end of this book for another example of this):

Figure 2.2 – Hovering shows that the type of once()’s output matches the type of its input

If you’re not still used to TypeScript, let’s see the pure JavaScript equivalent, which is the same code but for typing:

// once_JS.js

const once = (fn) => {

let done = false;

return (...args) => {

if (!done) {

done = true;

return fn(...args);

}

};

};

So, how would we use it? We first create a new version of the billing function.

const billOnce = once(billTheUser);

Then, we rewrite the onclick method as follows:

<button id="billButton" onclick="billOnce(some, sales, data)">Bill me </button>;

When the user clicks on the button, the function that gets called with the (some, sales, data) argument isn’t the original billTheUser() but rather the result of having applied once() to it. The result of that is a function that can be called only a single time.

You can’t always get what you want!

Note that our once() function uses functions such as first-class objects, arrow functions, closures, and the spread operator. Back in Chapter 1, Becoming Functional, we said we’d be needing those, so we’re keeping our word! All we are missing from that chapter is recursion, but as the Rolling Stones sang, You Can’t Always Get What You Want!

We now have a functional way of getting a function to do its thing only once, but how would we test it? Let’s get into that topic now.

Testing the solution manually

We can run a simple test. Let’s write a squeak() function that will, appropriately, squeak when called! The code is simple:

// once.manual.ts

const squeak = a => console.log(a, " squeak!!");

squeak("original"); // "original squeak!!"

squeak("original"); // "original squeak!!"

squeak("original"); // "original squeak!!"

If we apply once() to it, we get a new function that will squeak only once. See the highlighted line in the following code:

// continued...

const squeakOnce = once(squeak);

squeakOnce("only once"); // "only once squeak!!" squeakOnce("only once"); // no output

squeakOnce("only once"); // no output

The previous steps showed us how we could test our once() function by hand, but our method is not exactly ideal. In the next section, we’ll see why and how to do better.

Testing the solution automatically

Running tests by hand isn’t suitable: it gets tiresome and boring, and it leads, after a while, to not running the tests any longer. Let’s do better and write some automatic tests with Jest:

// once.test.ts

import once } from "./once";

describe("once", () => {

it("without 'once', a function always runs", () => {

const myFn = jest.fn();

myFn();

myFn();

myFn();

expect(myFn).toHaveBeenCalledTimes(3);

});

it("with 'once', a function runs one time", () => {

const myFn = jest.fn();

const onceFn = jest.fn(once(myFn));

onceFn();

onceFn();

onceFn();

expect(onceFn).toHaveBeenCalledTimes(3);

expect(myFn).toHaveBeenCalledTimes(1);

});

});

There are several points to note here:

- To spy on a function (for instance, to count how many times it was called), we need to pass it as an argument to

jest.fn(); we can apply tests to the result, which works exactly like the original function, but can be spied on. - When you spy on a function, Jest intercepts your calls and registers that the function was called, with which arguments, and how many times it was called.

- The first test only checks that if we call the function several times, it gets called that number of times. This is trivial, but we’d be doing something wrong if that didn’t happen!

- In the second test, we apply

once()to a (dummy)myFn()function, and we call the result (onceFn()) several times. We then check thatmyFn()was called only once, thoughonceFn()was called three times.

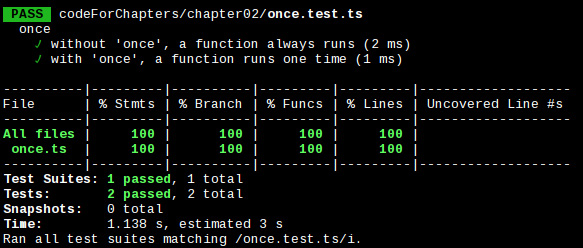

We can see the results in Figure 2.3:

Figure 2.3 – Running automatic tests on our function with Jest

With that, we have seen not only how to test our functional solution by hand but also in an automatic way, so we are done with testing. Let’s just finish by considering an even better solution, also achieved in a functional way.

Producing an even better solution

In one of the previous solutions, we mentioned that it would be a good idea to do something every time after the first click, and not silently ignore the user’s clicks. We’ll write a new higher-order function that takes a second parameter – a function to be called every time from the second call onward. Our new function will be called onceAndAfter() and can be written as follows:

// onceAndAfter.ts

const onceAndAfter = <

FNType extends (...args: any[]) => any

>(

f: FNType,

g: FNType

) => {

let done = false;

return ((...args: Parameters<FNType>) => {

if (!done) {

done = true;

return f(...args);

} else {

return g(...args);

}

}) as FNType;

};

We have ventured further into higher-order functions; onceAndAfter() takes two functions as parameters and produces a third one, which includes the other two within.

Function as default

You could make onceAndAfter() more powerful by giving a default value for g, such as () => {}, so if you didn’t specify the second function, it would still work fine because the default do-nothing function would be called instead of causing an error.

We can do a quick-and-dirty test along the same lines as we did earlier. Let’s add a creak() creaking function to our previous squeak() one and check out what happens if we apply onceAndAfter() to them. We can then get a makeSound() function that should squeak once and creak afterward:

// onceAndAfter.manual.ts

import { onceAndAfter } from "./onceAndAfter";

const squeak = (x: string) => console.log(x, "squeak!!");

const creak = (x: string) => console.log(x, "creak!!");

const makeSound = onceAndAfter(squeak, creak);

makeSound("door"); // "door squeak!!"

makeSound("door"); // "door creak!!"

makeSound("door"); // "door creak!!"

makeSound("door"); // "door creak!!"

Writing a test for this new function isn’t hard, only a bit longer. We have to check which function was called and how many times:

// onceAndAfter.test.ts

import { onceAndAfter } from "./onceAndAfter";

describe("onceAndAfter", () => {

it("calls the 1st function once & the 2nd after", () => {

const func1 = jest.fn();

const func2 = jest.fn();

const testFn = jest.fn(onceAndAfter(func1, func2));

testFn();

testFn();

testFn();

testFn();

expect(testFn).toHaveBeenCalledTimes(4);

expect(func1).toHaveBeenCalledTimes(1);

expect(func2).toHaveBeenCalledTimes(3);

});

});

Notice that we always check that func1() is called only once. Similarly, we check func2(); the count of calls starts at zero (the time that func1() is called), and from then on, it goes up by one on each call.