Chapter 7. DOM Manipulation and Events

The most important reason for JavaScript's existence is the web. JavaScript is the language for the web and the browser is the raison d'être for JavaScript. JavaScript gives dynamism to otherwise static web pages. In this chapter, we will dive deep into this relationship between the browser and language. We will understand the way in which JavaScript interacts with the components of the web page. We will look at the Document Object Model (DOM) and JavaScript event model.

DOM

In this chapter, we will look at various aspects of JavaScript with regard to the browser and HTML. HTML, as I am sure you are aware, is the markup language used to define web pages. Various forms of markups exist for different uses. The popular marks are Extensible Markup Language (XML) and Standard Generalized Markup Language (SGML). Apart from these generic markup languages, there are very specific markup languages for specific purposes such as text processing and image meta information. HyperText Markup Language (HTML) is the standard markup language that defines the presentation semantics of a web page. A web page is essentially a document. The DOM provides you with a representation of this document. The DOM also provides you with a means of storing and manipulating this document. The DOM is the programming interface of HTML and allows structural manipulation using scripting languages such as JavaScript. The DOM provides a structural representation of the document. The structure consists of nodes and objects. Nodes have properties and methods on which you can operate in order to manipulate the nodes themselves. The DOM is just a representation and not a programming construct. DOM acts as a model for DOM processing languages such as JavaScript.

Accessing DOM elements

Most of the time, you will be interested in accessing DOM elements to inspect their values or processing these values for some business logic. We will take a detailed look at this particular use case. Let's create a sample HTML file with the following content:

<html> <head> <title>DOM</title> </head> <body> <p>Hello World!</p> </body> </html>

You can save this file as sample_dom.html; when you open this in the Google Chrome browser, you will see the web page displayed with the Hello World text displayed. Now, open Google Chrome Developer Tools by navigating to options | More Tools | Developer Tools (this route may differ on your operating system and browser version). In the Developer Tools window, you will see the DOM structure:

Next, we will insert some JavaScript into this HTML page. We will invoke the JavaScript function when the web page is loaded. To do this, we will call a function on window.onload. You can place your script in the <script> tag located under the <head> tag. Your page should look as follows:

<html>

<head>

<title>DOM</title>

<script>

// run this function when the document is loaded

window.onload = function() {

var doc = document.documentElement;

var body = doc.body;

var _head = doc.firstChild;

var _body = doc.lastChild;

var _head_ = doc.childNodes[0];

var title = _head.firstChild;

alert(_head.parentNode === doc); //true

}

</script>

</head>

<body>

<p>Hello World!</p>

</body>

</html>The anonymous function is executed when the browser loads the page. In the function, we are getting the nodes of the DOM programmatically. The entire HTML document can be accessed using the document.documentElement function. We store the document in a variable. Once the document is accessed, we can traverse the nodes using several helper properties of the document. We are accessing the <body> element using doc.body. You can traverse through the children of an element using the childNodes array. The first and last children of a node can be accessed using additional properties—firstChild and lastChild.

Note

It is not recommended to use render-blocking JavaScript in the <head> tag. This slows down the page render dramatically. Modern browsers support the async and defer attributes to indicate to the browsers that the rendering can go on while the script is being downloaded. You can use these tags in the <head> tag without worrying about performance degradation. You can get more information at http://stackoverflow.com/questions/436411/where-is-the-best-place-to-put-script-tags-in-html-markup.

Accessing specific nodes

The core DOM defines the getElementsByTagName() method to return NodeList of all the element objects whose tagName property is equal to a specific value. The following line of code returns a list of all the <p/> elements in a document:

var paragraphs = document.getElementsByTagName('p');The HTML DOM defines getElementsByName() to retrieve all the elements that have their name attribute set to a specific value. Consider the following snippet:

<html>

<head>

<title>DOM</title>

<script>

showFeelings = function() {

var feelings = document.getElementsByName("feeling");

alert(feelings[0].getAttribute("value"));

alert(feelings[1].getAttribute("value"));

}

</script>

</head>

<body>

<p>Hello World!</p>

<form method="post" action="/post">

<fieldset>

<p>How are you feeling today?</p>

<input type="radio" name="feeling" value="Happy" /> Happy<br />

<input type="radio" name="feeling" value="Sad" />Sad<br />

</fieldset>

<input type="button" value="Submit" onClick="showFeelings()"/>

</form>

</body>

</html>In this example, we are creating a group of radio buttons with the name attribute defined as feeling. In the showFeelings function, we get all the elements with the name attribute set to feeling and we iterate through all these elements.

The other method defined by the HTML DOM is getElementById(). This is a very useful method in accessing a specific element. This method does the lookup based on the id associated with an element. The id attribute is unique for every element and, hence, this kind of lookup is very fast and should be preferred over getElementsByName(). -However, you should be aware that the browser does not guarantee the uniqueness of the id attribute. In the following example, we are accessing a specific element using the ID. Element IDs are unique as opposed to tags or name attributes:

<html>

<head>

<title>DOM</title>

<script>

window.onload= function() {

var greeting = document.getElementById("greeting");

alert(greeting.innerHTML); //shows "Hello World" alert

}

</script>

</head>

<body>

<p id="greeting">Hello World!</p>

<p id="identify">Earthlings</p>

</body>

</html>What we discussed so far was the basics of DOM traversal in JavaScript. When the DOM gets complex and you want sophisticated operations on the DOM, these traversal and access functions seem limiting. With this basic knowledge with us, it's time to get introduced to a fantastic library for DOM traversal (among other things) called jQuery.

jQuery is a lightweight library designed to make common browser operations easier. Common operations such as DOM traversal and manipulation, event handling, animation, and Ajax can be tedious if done using pure JavaScript. jQuery provides you with easy-to-use and shorter helper mechanisms to help you develop these common operations very easily and quickly. jQuery is a feature-rich library, but as far as this chapter goes, we will focus primarily on DOM manipulation and events.

You can add jQuery to your HTML by adding the script directly from a content delivery network (CDN) or manually downloading the file and adding it to the script tag. The following example shows you how to download jQuery from Google's CDN:

<html>

<head>

<script src="https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/2.1.4/jquery.min.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

</body>

</html>The advantage of a CDN download is that Google's CDN automatically finds the nearest download server for you and keeps an updated stable copy of the jQuery library. If you wish to download and manually host jQuery along with your website, you can add the script as follows:

<script src="./lib/jquery.js"></script>

In this example, the jQuery library is manually downloaded in the lib directory. With the jQuery setup in the HTML page, let's explore the methods of manipulating the DOM elements. Consider the following example:

<html>

<head>

<script src="https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/2.1.4/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script>

$(document).ready(function() {

$('#greeting').html('Hello World Martian');

});

</script>

</head>

<body>

<p id="greeting">Hello World Earthling ! </p>

</body>

</html>After adding jQuery to the HTML page, we write the custom JavaScript that selects the element with a greeting ID and changes its value. The strange-looking code within $() is the jQuery in action. If you read the jQuery source code (and you should, it's brilliant) you will see the final line:

// Expose jQuery to the global object window.jQuery = window.$ = jQuery;

The $ is just a function. It is an alias for the function called jQuery. The $ is a syntactic sugar that makes the code concise. In fact, you can use both $ and jQuery interchangeably. For example, both $('#greeting').html('Hello World Martian'); and jQuery('#greeting').html('Hello World Martian'); are the same.

You can't use jQuery before the page is completely loaded. As jQuery will need to know all the nodes of the DOM structure, the entire DOM has to be in-memory. To ensure that the page is completely loaded and in a state where it's ready to be manipulated, we can use the $(document).ready() function. Here, the IIFE is executed only after the entire documented is ready:

$(document).ready(function() {

$('#greeting').html('Hello World Martian');

});This snippet shows you how we can associate a function to jQuery's .ready() function. This function will be executed once the document is ready. We are using $(document) to create a jQuery object from our page's document. We are calling the .ready() function on the jQuery object and passing it the function that we want to execute.

This is a very common thing to do when using jQuery—so much so that it has its own shortcut. You can replace the entire ready() call with a short $() call:

$(function() {

$('#greeting').html('Hello World Martian');

});The most important function in jQuery is $(). This function typically accepts a CSS selector as its sole parameter and returns a new jQuery object pointing to the corresponding elements on the page. The three primary selectors are the tag name, ID, and class. They can be used either on their own or in combination with others. The following simple examples illustrate how these three selectors appear in code:

|

Selector |

CSS Selector |

jQuery Selector |

Output from the selector |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Tag |

|

|

This selects all the |

|

Id |

|

|

This selects single elements that have a |

|

Class |

|

|

This selects all the elements in the document that have the CSS class |

jQuery works on CSS selectors.

Note

As CSS selectors are not in the scope of this book, I would suggest that you go to http://www.w3.org/TR/CSS2/selector.html to get a fair idea of the concept.

We also assume that you are familiar with HTML tags and syntax. The following example covers the fundamental idea of how jQuery selectors work:

<html>

<head>

<script src="https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/2.1.4/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script>

$(function() {

$('h1').html(function(index, oldHTML){

return oldHTML + "Finally?";

});

$('h1').addClass('highlight-blue');

$('#header > h1 ').css('background-color', 'cyan');

$('ul li:not(.highlight-blue)').addClass('highlight-green');

$('tr:nth-child(odd)').addClass('zebra');

});

</script>

<style>

.highlight-blue {

color: blue;

}

.highlight-green{

color: green;

}

.zebra{

background-color: #666666;

color: white;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<div id=header>

<h1>Are we there yet ? </h1>

<span class="highlight">

<p>Journey to Mars</p>

<ul>

<li>First</li>

<li>Second</li>

<li class="highlight-blue">Third</li>

</ul>

</span>

<table>

<tr><th>Id</th><th>First name</th><th>Last Name</th></tr>

<tr><td>1</td><td>Albert</td><td>Einstein</td></tr>

<tr><td>2</td><td>Issac</td><td>Newton</td></tr>

<tr><td>3</td><td>Enrico</td><td>Fermi</td></tr>

<tr><td>4</td><td>Richard</td><td>Feynman</td></tr>

</table>

</div>

</body>

</html>In this example, we are selecting several DOM elements in the HTML page using selectors. We have an H1 header with the text, Are we there yet ?; when the page loads, our jQuery script accesses all H1 headers and appends the text Finally? to them:

$('h1').html(function(index, oldHTML){

return oldHTML + "Finally ?";

});The $.html() function sets the HTML for the target element—an H1 header in this case. Additionally, we select all H1 headers and apply a specific CSS style class, highlight-blue, to all of them. The $('h1').addClass('highlight-blue') statement selects all the H1 headers and uses the $.addClass(<CSS class>) method to apply a CSS class to all the elements selected using the selector.

We use the child combinator (>) to custom CSS styles using the $.css() function. In effect, the selector in the $() function is saying, "Find each header (h1) that is a child (>) of the element with an ID of header (#header)." For each such element, we apply a custom CSS. The next usage is interesting. Consider the following line:

$('ul li:not(.highlight-blue)').addClass('highlight-green');

We are selecting "For all list elements (li) that do not have the class highlight-blue applied to them, apply CSS class highlight-green. The final line—$('tr:nth-child(odd)').addClass('zebra')—can be interpreted as: From all table rows (tr), for every odd row, apply CSS style zebra. The nth-child selector is a custom selector provided by jQuery. The final output looks something similar to the following (Though it shows several jQuery selector types, it is very clear that knowledge of jQuery is not a substitute for bad design taste.):

Once you have made a selection, there are two broad categories of methods that you can call on the selected element. These methods are getters and setters. Getters retrieve a piece of information from the selection, and setters alter the selection in some way.

Getters usually operate only on the first element in a selection while setters operate on all the elements in a selection. Setters use implicit iteration to automatically iterate over all the elements in the selection.

For example, we want to apply a CSS class to all list items on the page. When we call the addClass method on the selector, it is automatically applied to all elements of this particular selection. This is implicit iteration in action:

$( 'li' ).addClass( highlighted' );

However, sometimes you just don't want to go through all the elements via implicit iteration. You may want to selectively modify only a few of the elements. You can explicitly iterate over the elements using the .each() method. In the following code, we are processing elements selectively and using the index property of the element:

$( 'li' ).each(function( index, element ) {

if(index % 2 == 0)

$(elem).prepend( '<b>' + STATUS + '</b>' );

});Chaining

Chaining jQuery methods allows you to call a series of methods on a selection without temporarily storing the intermediate values. This is possible because every setter method that we call returns the selection on which it was called. This is a very powerful feature and you will see it being used by many professional libraries. Consider the following example:

$( '#button_submit' )

.click(function() {

$( this ).addClass( 'submit_clicked' );

})

.find( '#notification' )

.attr( 'title', 'Message Sent' );xIn this snippet, we are chaining click(), find(), and attr() methods on a selector. Here, the click() method is executed, and once the execution finishes, the find() method locates the element with the notification ID and changes its title attribute to a string.

Traversal and manipulation

We discussed various methods of element selection using jQuery. We will discuss several DOM traversal and manipulation methods using jQuery in this section. These tasks would be rather tedious to achieve using native DOM manipulation. jQuery makes them intuitive and elegant.

Before we delve into these methods, let's familiarize ourselves with a bit of HTML terminology that we will be using from now on. Consider the following HTML:

<ul> <-This is the parent of both 'li' and ancestor of everything in

<li> <-The first (li) is a child of the (ul)

<span> <-this is the descendent of the 'ul'

<i>Hello</i>

</span>

</li>

<li>World</li> <-both 'li' are siblings

</ul>Using jQuery traversal methods, we select the first element and traverse through the DOM in relation to this element. As we traverse the DOM, we alter the original selection and we are either replacing the original selection with the new one or we are modifying the original selection.

For example, you can filter an existing selection to include only elements that match a certain criterion. Consider this example:

var list = $( 'li' ); //select all list elements // filter items that has a class 'highlight' associated var highlighted = list.filter( '.highlight ); // filter items that doesn't have class 'highlight' associated var not_highlighted = list.not( '.highlight );

jQuery allows you to add and remove classes to elements. If you want to toggle class values for elements, you can use the toggleClass() method:

$( '#usename' ).addClass( 'hidden' ); $( '#usename' ).removeClass( 'hidden' ); $( '#usename' ).toggleClass( 'hidden' );

Most often, you may want to alter the value of elements. You can use the val() method to alter the form of element values. For example, the following line alters the value of all the text type inputs in the form:

$( 'input[type="text"]' ).val( 'Enter usename:' );

To modify element attributes, you can use the attr() method as follows:

$('a').attr( 'title', 'Click' );jQuery has an incredible depth of functionality when it comes to DOM manipulation—the scope of this book restricts a detailed discussion of all the possibilities.

Working with browser events

When are you developing for browsers, you will have to deal with user interactions and events associated to them, for example, text typed in the textbox, scrolling of the page, mouse button press, and others. When the user does something on the page, an event takes place. Some events are not triggered by user interaction, for example, load event does not require a user input.

When you are dealing with mouse or keyboard events in the browser, you can't predict when and in which order these events will occur. You will have to constantly look for a key press or mouse move to happen. It's like running an endless background loop listening to some key or mouse event to happen. In traditional programming, this was known as polling. There were many variations of these where the waiting thread used to be optimized using queues; however, polling is still not a great idea in general.

Browsers provide a much better alternative to polling. Browsers provide you with programmatic means to react when an event occurs. These hooks are generally called listeners. You can register a listener that reacts to a particular event and executes an associated callback function when the event is triggered. Consider this example:

<script>

addEventListener("click", function() {

...

});

</script>The addEventListener function registers its second argument as a callback function. This callback is executed when the event specified in the first argument is triggered.

What we saw just now was a generic listener for the click event. Similarly, every DOM element has its own addEventListener method, which allows you to listen specifically on this element:

<button>Submit</button>

<p>No handler here.</p>

<script>

var button = document.getElementById("#Bigbutton");

button.addEventListener("click", function() {

console.log("Button clicked.");

});

</script>In this example, we are using the reference to a specific element—a button with a Bigbutton ID—by calling getElementById(). On the reference of the button element, we are calling addEventListener() to assign a handler function for the click event. This is perfectly legitimate code that works fine in modern browsers such as Mozilla Firefox or Google Chrome. On Internet Explorer prior to IE9, however, this is not a valid code. This is because Microsoft implements its own custom attachEvent() method as opposed to the W3C standard addEventListener() prior to Internet Explorer 9. This is very unfortunate because you will have to write very bad hacks to handle browser-specific quirks.

Propagation

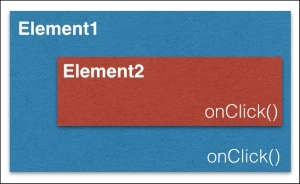

At this point, we should ask an important question—if an element and one of its ancestors have a handler on the same event, which handler will be fired first? Consider the following figure:

For example, we have Element2 as a child of Element1 and both have the onClick handler. When a user clicks on Element2, onClick on both Element2 and Element1 is triggered but the question is which one is triggered first. What should the event order be? Well, the answer, unfortunately, is that it depends entirely on the browser. When browsers first arrived, two opinions emerged, naturally, from Netscape and Microsoft.

Netscape decided that the first event triggered should be Element1's onClick. This event ordering is known as event capturing.

Microsoft decided that the first event triggered should be Element2's onClick. This event ordering is known as event bubbling.

These are two completely opposite views and implementations of how browsers handled events. To end this madness, World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) decided a wise middle path. In this model, an event is first captured until it reaches the target element and then bubbles up again. In this standard behavior, you can choose in which phase you want to register your event handler—either in the capturing or bubbling phase. If the last argument is true in addEventListener(), the event handler is set for the capturing phase, if it is false, the event handler is set for the bubbling phase.

There are times when you don't want the event to be raised by the parents if it was already raised by the child. You can call the stopPropagation() method on the event object to prevent handlers further up from receiving the event. Several events have a default action associated with them. For example, if you click on a URL link, you will be taken to the link's target. The JavaScript event handlers are called before the default behavior is performed. You can call the preventDefault() method on the event object to stop the default behavior from being triggered.

These are event basics when you are using plain JavaScript on a browser. There is a problem here. Browsers are notorious when it comes to defining event-handling behavior. We will look at jQuery's event handling. To make things easier to manage, jQuery always registers event handlers for the bubbling phase of the model. This means that the most specific elements will get the first opportunity to respond to any event.

jQuery event handling and propagation

jQuery event handling takes care of many of these browser quirks. You can focus on writing code that runs on most supported browsers. jQuery's support for browser events is simple and intuitive. For example, this code listens for a user to click on any button element on the page:

$('button').click(function(event) {

console.log('Mouse button clicked');

});Just like the click() method, there are several other helper methods to cover almost all kinds of browser event. The following helpers exist:

blurchangeclickdblclickerrorfocuskeydownkeypresskeyuploadmousedownmousemovemouseoutmouseovermouseupresizescrollselectsubmitunload

Alternatively, you can use the .on() method. There are a few advantages of using the on() method as it gives you a lot more flexibility. The on() method allows you to bind a handler to multiple events. Using the on() method, you can work on custom events as well.

Event name is passed as the first parameter to the on() method just like the other methods that we saw:

$('button').on( 'click', function( event ) {

console.log(' Mouse button clicked');

});Once you've registered an event handler to an element, you can trigger this event as follows:

$('button').trigger( 'click' );This event can also be triggered as follows:

$('button').click();You can unbind an event using jQuery's .off() method. This will remove any event handlers that were bound to the specified event:

$('button').off( 'click' );You can add more than one handler to an element:

$("#element")

.on("click", firstHandler)

.on("click", secondHandler);When the event is fired, both the handlers will be invoked. If you want to remove only the first handler, you can use the off() method with the second parameter indicating the handler that you want to remove:

$("#element).off("click",firstHandler);This is possible if you have the reference to the handler. If you are using anonymous functions as handlers, you can't get reference to them. In this case, you can use namespaced events. Consider the following example:

$("#element").on("click.firstclick",function() {

console.log("first click");

});Now that you have a namespaced event handler registered with the element, you can remove it as follows:

$("#element).off("click.firstclick");A major advantage of using .on() is that you can bind to multiple events at once. The .on() method allows you to pass multiple events in a space-separated string. Consider the following example:

$('#inputBoxUserName').on('focus blur', function() {

console.log( Handling Focus or blur event' );

});You can add multiple event handlers for multiple events as follows:

$( "#heading" ).on({

mouseenter: function() {

console.log( "mouse entered on heading" );

},

mouseleave: function() {

console.log( "mouse left heading" );

},

click: function() {

console.log( "clicked on heading" );

}

});As of jQuery 1.7, all events are bound via the on() method, even if you call helper methods such as click(). Internally, jQuery maps these calls to the on() method. Due to this, it's generally recommended to use the on() method for consistency and faster execution.

Event delegation

Event delegation allows us to attach a single event listener to a parent element. This event will fire for all the descendants matching a selector even if these descendants will be created in the future (after the listener was bound to the element).

We discussed event bubbling earlier. Event delegation in jQuery works primarily due to event bubbling. Whenever an event occurs on a page, the event bubbles up from the element that it originated from, up to its parent, then up to the parent's parent, and so on, until it reaches the root element (window). Consider the following example:

<html>

<body>

<div id="container">

<ul id="list">

<li><a href="http://google.com">Google</a></li>

<li><a href="http://myntra.com">Myntra</a></li>

<li><a href="http://bing.com">Bing</a></li>

</ul>

</div>

</body>

</html>Now let's say that we want to perform some common action on any of the URL clicks. We can add an event handler to all the a elements in the list as follows:

$( "#list a" ).on( "click", function( event ) {

console.log( $( this ).text() );

});This works perfectly fine, but this code has a minor bug. What will happen if there is an additional URL added to the list as a result of some dynamic action? Let's say that we have an Add button that adds new URLs to this list. So, if the new list item is added with a new URL, the earlier event handler will not be attached to it. For example, if the following link is added to the list dynamically, clicking on it will not trigger the handler that we just added:

<li><a href="http://yahoo.com">Yahoo</a></li>

This is because such events are registered only when the on() method is called. In this case, as this new element did not exist when .on() was called, it does not get the event handler. With our understanding of event bubbling, we can visualize how the event will travel up the DOM tree. When any of the URLs are clicked on, the travel will be as follows:

a(click)->li->ul#list->div#container->body->html->root

We can create a delegated event as follows:

$( "#list" ).on( "click", "a", function( event ) { console.log( $( this ).text() ); });

We moved a from the original selector to the second parameter in the on() method. This second parameter of the on() method tells the handler to listen to this specific event and check whether the triggering element was the second parameter (the a in our case). As the second parameter matches, the handler function is executed. With this delegate event, we are attaching a single handler to the entire ul#list. This handler will listen to the click event triggered by any descendent of the ul element.

The event object

So far, we attached anonymous functions as event handlers. To make our event handlers more generic and useful, we can create named functions and assign them to the events. Consider the following lines:

function handlesClicks(event){

//Handle click event

}

$("#bigButton").on('click', handlesClicks);Here, we are passing a named function instead of an anonymous function to the on() method. Let's shift our focus now to the event parameter that we pass to the function. jQuery passes an event object with all the event callbacks. An event object contains very useful information about the event being triggered. In cases where we don't want the default behavior of the element to kick in, we can use the preventDefault() method of the event object. For example, we want to fire an AJAX request instead of a complete form submission or we want to prevent the default location to be opened when a URL anchor is clicked on. In these cases, you may also want to prevent the event from bubbling up the DOM. You can stop the event propagation by calling the stopPropagation() method of the event object. Consider this example:

$( "#loginform" ).on( "submit", function( event ) {

// Prevent the form's default submission.

event.preventDefault();

// Prevent event from bubbling up DOM tree, also stops any delegation

event.stopPropagation();

});Apart from the event object, you also get a reference to the DOM object on which the event was fired. This element can be referred by $(this). Consider the following example:

$( "a" ).click(function( event ) {

var anchor = $( this );

if ( anchor.attr( "href" ).match( "google" ) ) {

event.preventDefault();

}

});Summary

This chapter was all about understanding JavaScript in its most important role—that of browser language. JavaScript plays the role of introducing dynamism on the web by facilitating DOM manipulation and event management on the browser. We discussed both of these concepts with and without jQuery. As the demands of the modern web are increasing, using libraries such as jQuery is essential. These libraries significantly improve the code quality and efficiency and, at the same time, give you the freedom to focus on important things.

We will focus on another incarnation of JavaScript—mainly on the server side. Node.js has become a popular JavaScript framework to write scalable server-side applications. We will take a detailed look at how we can best utilize Node.js for server applications.