When working on the bash shell and when you are sitting comfortably at your prompt eagerly waiting to type a command, you will most likely feel that it is a simple matter of typing and hitting the Enter key. You should know better than to think this, as things are never quite as simple as we imagine.

The bash command hierarchy

Command type

For example, if we type and enter ls to list files, it is reasonable to think that we were running the command. It is possible, but we often will be running an alias. Aliases exist in memory as a shortcut to commands or commands with options; these aliases are used before we even check for the file. Bash's built-in type command can come to our aid here. The type command will display the type of command for a given word entered at the command line. The types of command are listed as follows:

- Alias

- Function

- Shell built-in

- Keyword

- File

This list is also representative of the order in which they are searched. As we can see, it is not until the very end where we search for the executable file ls.

The following command demonstrates the simple use type:

$ type ls ls is aliased to 'ls --color=auto'

We can extend this further to display all the matches for the given command:

$ type -a ls ls is aliased to 'ls --color=auto' ls is /bin/ls

If we need to just type in the output, we can use the -t option. This is useful when we need to test the command type from within a script and only need the type to be returned. This excludes any superfluous information, and thus makes it easier for us humans to read. Consider the following command and output:

$ type -t ls alias

The output is clear and simple, and is just what a computer or script requires.

The built-in type can also be used to identify shell keywords such as if, and case. The following command shows type being used against multiple arguments and types:

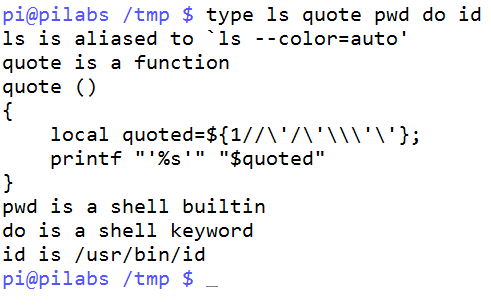

$ type ls quote pwd do id

The output of the command is shown in the following screenshot:

You can also see that the function definition is printed when we stumble across a function when using type.

Command PATH

Linux will check for executables in the PATH environment only when the full or relative path to the program is supplied. In general, the current directory is not searched unless it is in the PATH. It is possible to include our current directory within the PATH by adding the directory to the PATH variable. This is shown in the following command example:

$ export PATH=$PATH:.

This appends the current directory to the value of the PATH variable; each item in the PATH is separated using a colon. Now your PATH has been updated to include the current working directory and, each time you change directories, the scripts can be executed easily. In general, organizing scripts into a structured directory hierarchy is probably a great idea. Consider creating a subdirectory called bin within your home directory and add the scripts into that folder. Adding $HOME/bin to your PATH variable will enable you to find the scripts by name and without the file path.

The following command-line list will only create the directory, if it does not already exist:

$ test -d $HOME/bin || mkdir $HOME/bin

Although the preceding command-line list is not strictly necessary, it does show that scripting in bash is not limited to the actual script, and we can use conditional statements and other syntax directly at the command line. From our viewpoint, we know that the preceding command will work whether you have the bin directory or not. The use of the $HOME variable ensures that the command will work without considering your current filesystem context.

As we work through the book, we will add scripts into the $HOME/bin directory so that they can be executed regardless of our working directory.